Importance of allowing your dog to sniff

Importance of allowing your dog to sniff

I peek out the front door to check on my dog, who is sunning himself in his favourite spot in the sun. He is lying on an old moving trolley, since repurposed to give him a boost up to the sunrays, which don’t reach the ground at this time of morning. As I stick my head out the door, he lifts his nose, and I can see his nostrils gently flare in and out as he recognizes I am close. He does not see me with his eyes, as they are squinted shut due to the sun, but he sees me with his nose.

There are many more examples of my dog using his nose to see. When I return from the shops, and we greet enthusiastically, my human tendency is to reach out and touch to say hello, but he ducks away, preferring to sniff my hands first to see where I have been. (If you have not already read about the human as opposed to canine perspective of greeting, it is worth reading ‘How do you greet a dog politely’). When I return from volunteering at the dog shelter, he sniffs my shoes and clothes carefully. I get the full pat down with the nose. If I offer him something, whether it is an object or food, he does not use his eyes to examine the item further; he sniffs it.

On one occasion, when out on a walk with my dog, he stopped, hesitant to go further. I surveyed the pavement ahead. It seemed clear. I thought he was being overly sensitive and encouraged him to continue. As we passed the parked cars ahead, hiding behind the wheel of the last car was a cat. I felt very foolish. My dog was right – there was something ahead! He had seen it with his nose. I should have listened. Being human, I had immediately dismissed what I could not see with my eyes. On another occasion, he started sniffing the ground very attentively, seemingly following a trail back and forth, as he narrowed in on the direction of the scent trail. Looking ahead to see what had taken his interest, it was easy for me to quickly spot a scattering of nacho chips that had been discarded on the pavement. This time my eyesight won out against my dog’s nose, and I was able to divert him away.

Even with these simple observations, it is apparent how often my dog uses his nose and scent to make sense of and navigate his environment.

It is understandable why the use of olfaction may be the predominant sense for dogs. It is estimated that dogs have 300 million olfactory receptor cells; in comparison humans have about 5 million. Dogs have the ability of smelling with each nostril on an individual basis, allowing them to distinguish the direction of the scent. The slits on the side of the nose allow for the old air to exit at the same time as the dog is breathing in new air through the nostrils, allowing the dog to take in scent continuously. The air is separated and passes through an area at the back of the nose that has a labyrinth of scroll-like bony structures called turbinates. The air is filtered through the turbinates for olfaction, while some of the air follows a separate route down the pharynx for respiration. The air that humans take in for respiration and scent is not separated, going in and out with the air that we smell. Additionally, dogs have a secondary olfactory organ called the vomeronasal organ that allows dogs to detect pheromones and non-volatile chemicals. There are times where you can spot the dog using his vomeronasal organ, as he will display a tonguing response. The dog may chatter his teeth or drool a bit at the mouth as he deciphers the components of the scent. To interpret all this information, a larger percentage of the dog’s brain is used to process scent, with the olfactory bulb taking up more area of the brain than it does in humans. The dog can detect smells at concentrations of 100 million times less than our noses can detect.

In Alexandra Horowitz’s book, ‘Being a Dog: Following the Dog Into a World of Smell’, she gives an example of scientific research to test scent thresholds of detection dogs. One of the tests was how diluted an odour could become before the dog would struggle to detect the odour. The scent of amyl acetate (smell of banana) had to be distinguished from non amyl acetate canisters. The dog kept finding the scent until it was diluted to the equivalent of a couple of drops of amyl acetate to one trillion drops of water.

It is estimated that dogs have 300 million olfactory receptor cells; in comparison humans have about 5 million.

The following Ted-Ed video lesson by Alexandra Horowitz gives a good summary of the dog’s sense of smell and why dogs are physically able to process scent so efficiently. For an in-depth look at how dogs perceive the world with their noses, it is well worth reading Alexandra Horowitz’s book, ‘Being a Dog: Following the Dog Into a World of Smell’.

Imagine visiting an art gallery if every time you attempted to look at a painting, you were forced to move along and had your eyes covered, missing the chance to get a glimpse of the painting. How frustrating an experience would that be? As humans, we do not have the same level of perception and therefore discount dogs’ levels of sensory perception far too many times, especially when giving them opportunities to interact with the environment. Too often I have seen guardians impatiently yanking their dogs away if the dog stops to sniff even for a moment. I have observed dogs that are walked obediently to heel and not permitted to stray to sniff, dogs walked with equipment that does not allow them to dip their noses down or move their heads or bodies with ease, or walks that are carefully curated from a human perspective, where the walk is a quick march for exercise purposes and stopping is not tolerated. The mental stimulation from sniffing and exploring can be just as tiring as physical exercise.

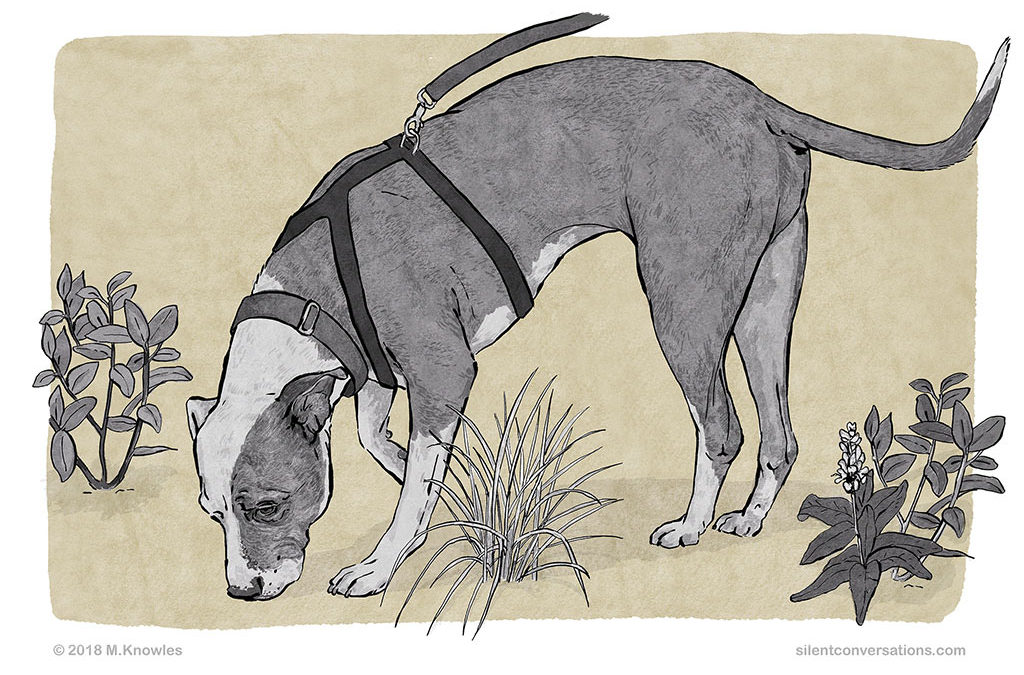

If my dog responds to an environment in a manner in which he is comfortable to investigate it – in an in-depth manner with calm sniffing – this indicates that the walk is going well and the environment is suitable for him. If my dog is pulling, moving erratically and choosing not to engage with the environment by sniffing, this is a telltale sign that he is not coping for some reason. So sniffing calmly and engaging with the environment can give clues as to the internal state of your dog. A good walk for my dog would be one in which he meanders with a calm, loose, slow-moving body, taking his time to stop at various spots to sniff and investigate. To do so, the leash needs to be long enough for him to move comfortably, and the equipment he is wearing should not hinder him from being able to reach the ground with his nose easily. The choice of walk should be individual for each dog; certain environments or times or the duration of a walk can be too stimulating for some dogs. A dog may not have the appropriate skill level or coping skills for a particular environment, or the dog’s stress level may be too high to cope with a particular walk.

How your dog engages with the environment by sniffing, and in which context he does so, can give vital clues as to how comfortable your dog is feeling and if he is coping within an environment.

There is another important reason to pay attention to your dog’s sniffing. On certain occasions, sniffing plays a part in how dogs communicate. If you have not already read the dog body language article about sniffing, you can read about it here.

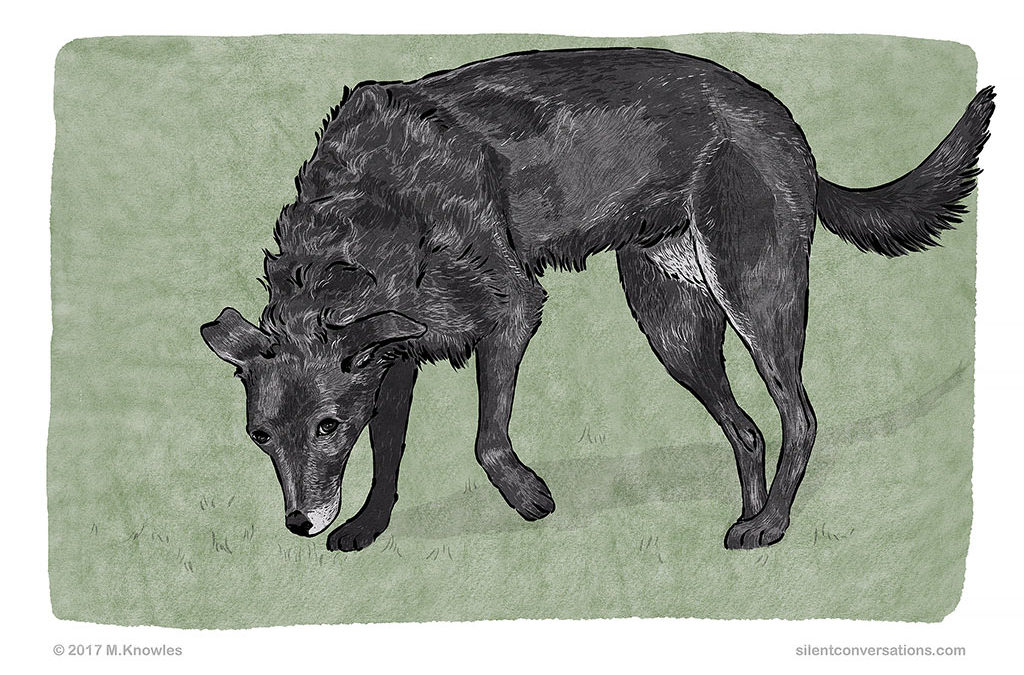

The dog may stop to sniff as a calming signal or negotiation. For example, a dog may use sniffing the ground at a distance in the beginning stages of approaching another dog. A slow non-direct approach is polite, and it gives each party the opportunity to negotiate at a distance. In another context, sniffing could be used as a way to defuse a situation; one dog may walk away sniffing the ground, encouraging the other dog to mirror him, defusing the interaction.

Depending on context, sniffing the ground could also be displacement behaviour or a stress response. If the dog is unsure of something ahead, he may slow and start sniffing the ground, showing he may be feeling conflicted. It is vital to allow your dog to express himself and to observe your dog’s body language so you can offer support in such situations.

I mentioned an example of when my dog chooses to sniff the ground as displacement when he feels uncomfortable, in this article: ‘Considering the effects of walking or running straight towards a dog’.

The body language that occurs when a dog starts sniffing due to displacement can be subtle. It is crucial to observe changes in the environment, noting the dog’s whole body and body posture, as well as movement and body language signals. For instance, a dog may see something ahead, pause, and then subtly curve his body away from the object that is causing discomfort. He may then do some displacement sniffing. It is worth observing how he sniffs; some displacement sniffing may seem less focused than when a dog is actively investigating a scent. In other instances, it can seem out of place, as the dog suddenly finds a spot to sniff intently. The dog may use the moment of sniffing as a surreptitious way of surveying the environment, so it is important to observe where the gaze of the eyes falls. The dog may also move his ears, perhaps to the side slightly, in order to use his other senses to gather further information. One should pay attention to the subtleties.

Scent is the predominant way in which dogs make sense of their world. Sniffing is vital to the way dogs gather information and interact with their environment. At times, depending on the context, a dog is not just sniffing a scent; he is communicating. What he is communicating can vary according to the circumstances, so it is worth paying attention in order to be a supportive partner. Allowing your dog to interact fully with his environment and express himself with ease ensures a stronger, mutually connected relationship between dog guardian and dog.

A video tribute to the twitching nose and the scents in the breeze.

Martha Knowles

Author

My vision is to create a community of dog guardians who share their observations and interpretations of their dogs’ silent conversations. Hopefully, these experiences and stories will provide some insight into dog communication, which is often overlooked by the untrained eye because it is unfamiliar to humans. We are accustomed to communicating mainly with sound, so we are not attuned to the silent subtle gestures and body language used by dogs to communicate. If you take the time to observe, you will start to see these 'silent conversations' going on around you. My dream is for dog communication to become common knowledge with all dog guardians and as many people as possible. Surprisingly, there are still some professionals working in various dog-related careers who are uneducated about dog body language. Greater awareness of how dogs communicate will help to provide better understanding and improve the mutual relationship between dogs and humans. This will promote safer interactions between our two species and hopefully remove some of the expectations placed on dogs within human society. I would like dog guardians to feel empowered with their knowledge of dog communication so that they can be their dogs’ advocates and stand up for themselves and their dogs when it really matters.