Sitting – Dog Body Language

Sitting – Dog Body Language

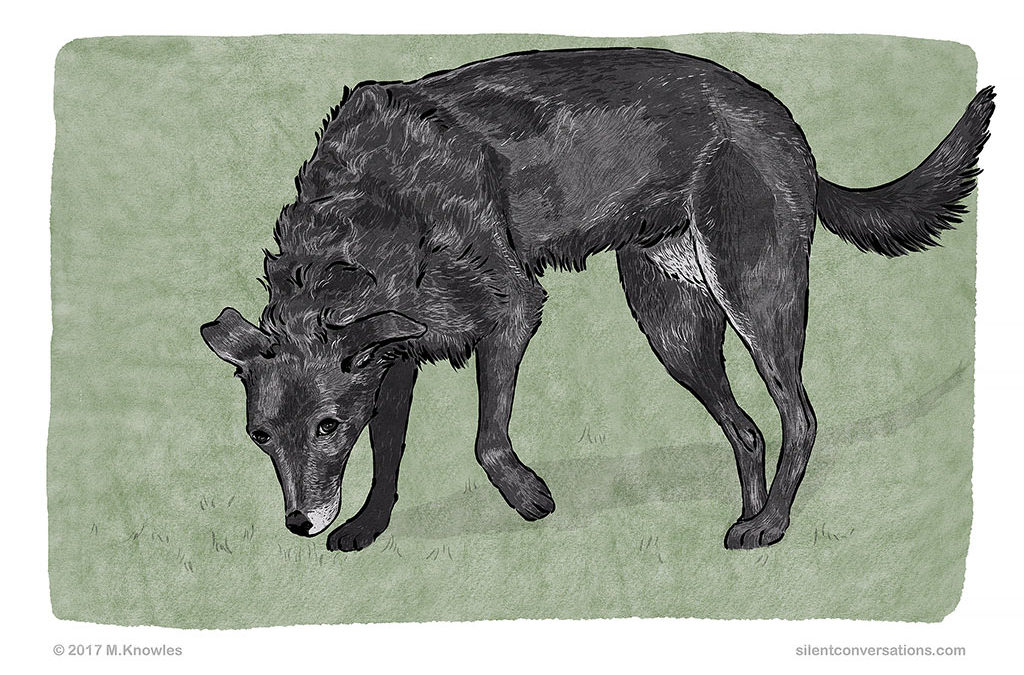

In dog body language, sitting is a very clear body language signal that is unmistakably visible when offered. It may be used to communicate clearly to another dog that no harm is intended. It could be offered as a gesture of goodwill to a dog that may be feeling a bit uncomfortable within an interaction, or it may be used to calm an interaction down.

Here are a couple of examples of situations where a dog may offer a sit:

-

A young pup is interacting with a variety of passing adult dogs in an off lead area. She is keen to interact and greet each passing dog but finds herself a bit out of her depth at times, so I can see why she may have chosen to sit as a strategy of communication when greeting. Still honing her skills of polite greetings, she wavers between being slightly unsure and obviously nervous, which may come across in her bounding about in a playful puppy manner at times if a situation becomes a little awkward. With this particular interaction, an adult dog is rather pushy with his greeting. The adult dog approaches the puppy quickly, coming in quite close to her. His tail is wagging really fast, his ears are to the side and slightly raised, and his head is up. He tries to sniff the puppy’s face and back and keeps bumping into her while attempting to place his chin on her shoulder. His movements are jerky and quite fast. This behaviour could be interpreted as bullying. She immediately chooses to sit, crouching down slightly. Her ears are back, and with soft, blinking eyes, she attempts several head turns. Interestingly, at this point a third dog intervenes to split the pair, moving the adult dog on. Perhaps both the puppy and the adult dog are struggling and do not have the skills to cope with the interaction. Read more about splitting behaviour in this relating story.

-

Two dogs approach each other in a curve to greet. One dog pauses, whilst the other dog stops and sniffs the face of the first dog. As she gently sniffs around his face, he does a head turn. They both curve around, and she sniffs underneath him and then starts sniffing his rear end. He does quick head turns and keeps his eye on her. She sniffs his rear end for a while. He takes a few steps away and sniffs the ground, but she follows and continues sniffing. He does a lip lick, his ears are slightly back, and, with his body slightly crouched, he curves around to look back at her. He decides to sit, and then she curves away, walking on to sniff an area nearby. The message is clear: he sits to communicate his discomfort with the prolonged sniffing and wants to calm the situation. She listens to his clear message and decides to walk away and give him a bit more space.

-

There is a dog sitting quite still in the corner of the room, at the far end. He is avoiding eye contact with anyone in the room and is choosing to stay as far away as possible. He is not feeling comfortable and is trying to be as inconspicuous as he can because he does not wish to interact. Another dog tries to befriend him. She approaches slowly in a curve but tries to sniff his face. He snaps at her, giving her a warning to back off. Immediately afterwards, he turns his head away and remains still. She hops away from the snap, gives him space, and sits a distance away, avoiding any eye contact and keeping her body parallel and side-on to him. She sits for a while, hoping this will calm the situation and he will realize she means no harm. He continues to keep his head turned, so she decides to get up and walk away, as it is clear he does not wish to interact, even with her calming signal of sitting. In this situation, there are two different sits occurring: the one dog sits to show he is no threat but wishes to be left alone, and the other dog sits in the hope of facilitating interaction by offering a calming signal that communicates no threat.

-

A puppy is trying to play with an older dog and jumping around in front of her. The older dog is not interested and has given the puppy a few head turns to try to calm the situation and show she does not wish to interact in this manner. He continues and is not listening. She walks away and sits down with her back to him, communicating even more loudly that she is not willing to interact with him until he calms down.

These are just a few examples; there may be many more. Start observing to see if you can notice any sitting in different contexts. As discussed below, interpretations such as the above examples should not be attempted without careful observation and consideration of all aspects of the situation.

A few notes to consider when observing dog body language

Observation before interpretation

Interpretations should be offered only once you have observed the complete interaction and taken note of the wider picture. To offer an unbiased interpretation of the body language, observe and take note of the situation, taking into account the dog’s whole body, the body language signals, and environment first before offering an interpretation. List all the body language you see in the order that it occurs; try to be as descriptive as possible without adding any emotional language. For instance, saying a dog looks happy is not descriptive and would be seen as an interpretation rather than an observation.

You could, however, list what you observe: ears to the side, eyes almond shaped, slight shortening of the eye, mouth open, long lips, tongue out, body moving loosely, body facing side-on, tail wagging at a slow, even pace at body level.

From the observation, I could interpret that the dog seems relaxed or comfortable. I still prefer to say relaxed rather than happy, as I feel you will truly never know exactly what the dog may be feeling on the inside emotionally. It is quite likely the dog may be feeling happy, but I prefer to comment on how the dog is behaving in response to the situation rather than presuming internal emotional states.

The importance of viewing body language within context

Interpretations can vary depending on the context. It is possible for certain body language to be used in different contexts and have subtle differences in meaning within those contexts. Individual body language signals should not be observed in isolation; the wider picture should be considered. Take note of what the dog’s body as a whole is saying. Keep in mind each dog is an individual with varying skills and experiences. What may be typical for one individual may not be for another. In order to observe body language in context, consider the following: the situation, body language signals, the body language expressed by all parts of the dog’s body, the environment, and the individuals involved. It is worth noting how the body language changes with feedback from the environment or the other individuals interacting.

Martha Knowles

Author

My vision is to create a community of dog guardians who share their observations and interpretations of their dogs’ silent conversations. Hopefully, these experiences and stories will provide some insight into dog communication, which is often overlooked by the untrained eye because it is unfamiliar to humans. We are accustomed to communicating mainly with sound, so we are not attuned to the silent subtle gestures and body language used by dogs to communicate. If you take the time to observe, you will start to see these 'silent conversations' going on around you. My dream is for dog communication to become common knowledge with all dog guardians and as many people as possible. Surprisingly, there are still some professionals working in various dog-related careers who are uneducated about dog body language. Greater awareness of how dogs communicate will help to provide better understanding and improve the mutual relationship between dogs and humans. This will promote safer interactions between our two species and hopefully remove some of the expectations placed on dogs within human society. I would like dog guardians to feel empowered with their knowledge of dog communication so that they can be their dogs’ advocates and stand up for themselves and their dogs when it really matters.